Time Present and Time Past

Mark Patton's Blog

Sunday, 7 May 2023

On Being an Islander: Reflections on Current Exhibitions in Oxford and Cambridge

As an islander myself (born and brought up on the Channel Island of Jersey, and having lived all but one year of my life on islands and archipelagoes, including the UK "mainland," on which I live today), I have an inevitable interest in such topics. Back in 1996, I published a book, Islands in Time: Island Sociogeography and Mediterranean Prehistory(Routledge). In it, I sought to adapt the long-standing "Theory of Island Biogeography," used by biologists around the world, to the very different data-sets of archaeology, and the study of human communities. Island Biogeography Theory makes use of physical variables, such as island size, and distance from adjacent mainlands, to understand the processes of colonisation of islands by animal and plant species, and the probability of their survival in an insular environment. It has long been understood that evolution on islands can produce "endemic" species that occur nowhere else, including, famously, the marine iguanas and giant tortoises of the Galapagos Islands.

Summary diagram of Island Biogeography Theory, from B.H. Warren et al. 2015, in Ecology Letters 18, 200-217.

I was struck, in the 1990s, by possible archaeological corollaries of such phenomena, which I termed "cultural elaborations:" the Minoan "palaces" of Crete occur nowhere else in the Mediterranean; likewise the stone temples of Neolithic Malta; and the Bronze Age towers known as nuraghe, on Sardinia. On the other hand, as Mary Beard has pointed out in a contribution to the Fitzwilliam exhibition, islands, in archaeological terms, can be as much about "connectedness" as about isolation. The early 20th Century ethnographer, Bronislaw Malinowski, in his famous study (Argonauts of the Western Pacific) of elaborate exhange networks on the Trobriand Islands, to the north of Papua New Guinea, showed how such "connectedness" could be a medium for the emergence of social complexity in island communities.

The stone temple of Ggantija on Gozo, Malta, 3600-2500 BC. Photo: BoneA, Licensed under CCA.

Nuraghe Losa, Sardinia, 13th-14th Century BC. Photo: Elena at Italian Wikimedia (image is in the Public Domain).

Nuraghic bronze warrior figurines from Sardinia, 1000-700 BC. Photo: Prc90, Licensed under CCA.

Unsurprisingly, the case studies that I used in my 1996 book are, by any modern standard, thoroughly out of date, yet many of the same questions about island societies continue to suggest themselves. Geographically, of course, there is a world of difference between Crete, Cyprus, and Sardinia, on the one hand; and the true "oceanic" insularity of, say, the Galapagos, Easter Island, or even the Trobriand Islands, on the other. These, however, are differences of degree, rather than differences of kind.

The Oxford exhibition focusses specifically on the site of Knossos, on Crete, the largest and longest-enduring of the Minoan "palaces" of Crete. One of my students recently asked whether "palace" was really the most appropriate term for these extraordinary buildings. Neither he nor I could suggest a better term, but the problem is a real one: they were clearly, at least in part, residential complexes, and the principal residents must surely have belonged to an elite, but there is none of the abundant evidence for "kingship" that one finds in contemporary Mesopotamia (Iraq) or Egypt, until the very end of the "palatial period," when it seems to have been introduced by Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland.

The Palace of Knossos. Photo: Lapplaender, Licensed under CCA.

"Kamares Ware" pottery from Crete, c1800-1700 BC. This distinctive pottery seems to have been produced in workshops closely associated with the palaces themselves, but some vessels were exported, and have been found as far away as Egypt, attesting to Minoan Crete's "connectedness" to the wider world of the eastern Mediterranean. Photo: Bernard Gagnon, Licensed under CCA.

"Marine Style" ewer from Poros, Crete, 1500-1450 BC, on display at the Ashmolean Museum. This style seems to have emerged at Knossos in the aftermath of the destruction of Crete's other palaces, possibly as a result of a tsunami following the catastrophic eruption on the neighbouring island of Thera. Photo: Mark Patton, Licensed under CCA.

Whilst most of the objects on display at the Ashmolean come either from the museum's own collection, or from the Heraklion Museum on Crete, those on display at the Fitzwilliam are drawn from a wider range of collections, and vary, in date, from the time of the Mediterranean's first farming communities, more than ten thousand years ago, to the flourishing of Greek and Roman civilisation between the Fifth Centuries BC and AD.

Marble figurines from the Cycladic Islands, 2800-2000 BC, made, probably on the island of Naxos, and widely exhanged around the Aegean, probably before the age of sail. Photo: Sailko, Licensed under CCA.

There is a superabundance of extraordinary artefacts on display in both exhibitions, and questions are thrown up, to which, it seems, there are no more definitive answers available in 2023 than there were in 1996, although there are, incontestibly, more sites known, and more artefacts excavated and catalogued, and, thus, available to display.

For those, like myself, with an appetite for still more, both exhibitions are accompanied by a lively programme of events, and we have to hope that these will, in some way, be brought together and conserved as a permanent legacy of two exhibitions that I, for one, will not be forgetting any time soom.

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

Sunday, 9 January 2022

Thomas Lambe, Soap-Boiler and Baptist Preacher: A Religious and Political Radical in 17th Century London

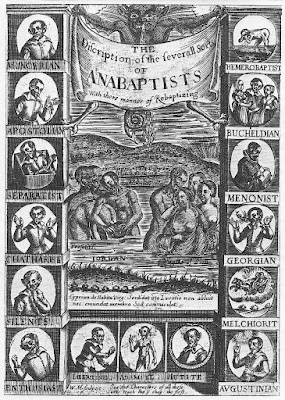

This blog-post is a summary of research that I carried out for the Worshipful Company of Tallow Chandlers, during the course of 2020 and 2021, and presented to the company in November, 2021. Thomas Lambe, a freeman of the company in the early decades of the 17th Century, was a soap-boiler (a producer of soap from rendered animal fat - an activity forming part of the craft and mystery of tallow-chandlery as defined at the time), who was also a controversial Baptist preacher, and a leading member of the "Levellers," a radical political movement agitating for universal manhood suffrage (the vote for every adult male), fixed-term parliaments, the abolition of capital punishment for theft, and the abolition of imprisonment for debt.

|

| London in the late 16th Century. |

|

| Illustration from The Declaration and Standard of the Levellers of England, 1649. |

Several of the most widely read recent books on the "Leveller" movement (a label rejected by most of its supporters, on the grounds that they did not support the "levelling of mens' estates," except on a purely voluntary basis), including John Rees's The Leveller Revolution, state that Lambe was one of two tallow chandlers involved in its leadership, the other being Thomas Prince. I did not, however, find Prince's name in the membership records of the company, and nor could I find any particular reason why Prince, who made his living as a cheese-monger, should have been a member of it. Prince is a fascinating historical figure in his own right, but my research focused on Thomas Lambe (to confuse matters further, there seem to have been two Baptist preachers named Thomas Lambe active in London at the same time; one described as a soap-boiler, the other as a merchant; and I am writing only about the former).

Thomas Lambe seems to have been born at Colchester, where he may also have served an apprenticeship as a tallow chandler and soap-boiler. I was unable to trace a baptismal record for him, but he did marry Dorcas Prentice there in 1619. Whilst living in Colchester, the couple fell foul of the authorities several times: they were excommunicated in 1636, for failing to attend (Anglican) worship, and for refusing to have one of their children baptised; the following year, still in Colchester, Thomas was arrested for "soap-boiling on the Sabbath."

Thomas Lambe seems to have taken up residence in London by 1624 (the date at which his name first appears in the membership records of the Tallow Chandlers). The fact that his name appears, in the 1620s and 1630s, both in London and in Colchester, might suggest that he and Dorcas had two homes, the one in Colchester very possibly shared with one or more of their parents. Thomas was imprisoned in the Fleet Gaol in 1640, for unlicensed preaching in Whitechapel (provoking a riot when constables attempted to break up the meeting); but, by 1641, had established a Baptist congregation in Bell Alley (off Coleman Street, near the Guildhall); by this time, he seems to have been permanently resident in London. He undertook several preaching tours of England, visiting Guildford, Portsmouth, & Devizes; and baptising people in the Severn and the Colne (he seemingly had more sense than to do so in the filthy waters of the Thames at London).

|

| "The Dippers Dipp'd," from an anti-Baptist pamphlet by Daniel Featley (1649), portraying Baptists as schismatics. |

Lambe's congregation in Bell Alley soon gained a reputation for religious radicalism. The Presbytereian, Thomas Edwards, complained about the role of "mechanicks" (artisans and working people, without formal training in theology) in preaching: Lambe even encouraged women, including a lace-maker, Mrs Attaway, to preach in his church, someting that would not have been permitted in more conventionally "Puritan" congregations (few people in 17th Century England considered themselves to be "Puritans" - the term was almost always used in a derogatory sense, to refer to people who saw themselves as Presbyterians, "Independents" - in modern terms Congregationalists, Baptists, and Quakers). Edwards (whose agenda was to extinguish all forms of "Puritanism" other than his own) raised further objections to Lambe's congregation:

"Many use to resort to this church and meeting, the house and yards full, especially young youths and wenches flock thither ... in the latter end of the Lord's Day, many persons, some from the separate churches [Independent, Quaker], others from our churches [formerly Anglican, converted to Presbyterian worship], will go to this Lambe's church for novelty, because of the disputes and wranglings that will be there upon questions ... several parties in one room, some speaking in one part, some in another ... "

|

| Bell Alley, 17th Century plan. |

Among the questions thus debated by Lambe's congregants was the suggestion, heretical to men such as Edwards, of "universal reconciliation," according to which everyone (or, at the very least, all Christian believers) would ultimately be saved, through the boundless love and grace of Jesus Christ.

Lambe was a close associate of Richard Overton, also a Baptist (and thus probably a member of Lambe's congregation), and a "Leveller," who ran an undreground printing operation from Bell Alley.

The Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, holds one of very few surviving copies of Lambe's Treatise of Particular Predestination, printed by Overton, which argues that:

" ... the spirit of the Gospel, which holds forth Christ's giving himself, a ransom for all men [1 Tim, 6], a propitiation for the sinnes of the whole world [1 John, 2,2], and that he tasted death for every man [Heb.2.9], which is such a glorious truth, as without which first the Gospel of God's free grace cannot be preached to all men."

He goes on, in this pamphlet, to argue against the Calvinist notion (accepted by most Presbyterians and Independents, as well as by many less radical Baptists) that only some people have been chosen by God for salvation.

In 1641, as the battle lines were being drawn up between Charles I and Parliament, "Puritans" within the City of London (already, probably, in a small majority) staged an effective coup, replacing all, or nearly all, of the Anglicans and Royalists on the Common Council with Presbyterians and Independents whose loyalty was to Parliament. Isaac Pennington became the first in a line of "Puritan" Lord Mayors. The new administration quickly formed a "Committee of Safety," and took control of the "London Trained Bands." This militia, which had served for many years as a police and civil defence force, and as an informal fire brigade, would become the backbone of the Parliamentary Infantry, under the command of Philip Skippon, a Presbyterian who had served as a mercenary, on the Protestant side, in the Thirty Years War in Germany. If Thomas Lambe had ever served in the Trained Bands, it would have been in the 1620s, when he was first living in London. Although we do not know when he was born, his date of marriage suggests that, by the 1640s, he would probably have been considered too old for front-line military service.

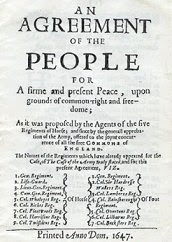

Whilst he probably played no active role in the civil wars themselves, he was certainly engaged in the attempt to define the new society that it was hoped would emerge from them. Together with his friends, the printer, Richard Overton; the cheese-monger, Thomas Prince; and other prominent Londoners, including John Lilburne; he was a member of the "Levellers," a movement which some have seen as England's first political party. Initially, in the 1640s, it was a loose alliance of men, who met to discuss political topics, in taverns including The Windmill and The Whalebone, both in Lothbury. One such discussion group was the "Robin Hood Club," and the association with the legendary outlaw was more than accidental. Later, members of these various discussion groups took to wearing a sea-green ribbon, as a means of identifying themselves.

A "Leveller" manifesto of 1649, signed by Lilburne, Prince, and Overton, sets out what they thought to be at stake: " ... an opportunity which, these 600 years, has been desired, but could never be obtained, of making this a truly happy and wholly free nation ... "

|

| A "Leveller" manifesto, 1647. |

The "Levellers" seem to have been a genuinely grass-roots movement, led by artisans and "mechanicks," rather than by intellectuals. Leaving aside John Milton's Areopagitica (1644), which many of these men might indeed have read, but the title of which probably meant little to them, radical tracts of the time, including "Leveller" pamphlets, do not draw their inspirations from the examples of either the Athenian Democracy, or the Roman Republic, nor do they make reference to the constitutional example of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Instead, they draw on folk traditions of Anglo-Saxon resistance to Norman rule (seeing Charles Stuart as the successor of William the Conqueror), including the mythical example of Robin Hood, and the supposedly "consensual" or constitutional basis of rule by the Anglo-Saxon Kings, including Alfred the Great.

Here, for example, is Gerard Winstanley, writing in 1649 (and criticising not Charles Stuart, who by that stage was dead, but the "Puritan" establishment of the Commonwealth itself):

"O what mighty delusion, do you, who are the powers of England, live in! That while you pretend to throw down the Norman yoke, and Babylonish power, and have promised to make the groaning people of England a Free People; yet you still lift up that Norman yoke, and slavish tyranny, and holds the People as much in bondage, as the Bastard Conquerour himself, and his Councel of War."

The "Leveller" manifestoes of 1648-49 were radical indeed, including commitments to "manhood suffrage" (the right of every man, possibly excluding servants, to vote); fixed term (biennial) parliaments; "absolute" freedom of religion (it is a little unclear whether this was intended to include Roman Catholics or Jews); the abolition of capital punishment for theft; and the abolition of imprisonment for debt. For so long as these were simply matters for discussion in London taverns, Presbyterians and "Silken" (presumably well-heeled and socially conservative) Independents paid little attention to them, but, by 1647, "Leveller" opinions were gaining currency within the ranks of the New Model Army, which senior commanders, including Oliver Cromwell, took far more seriously.

In the Putney Debates, chaired by Cromwell, and prompted by arrears in pay to soldiers, the "Leveller," Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, argued that:

"I think that the poorest hee that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest hee; and therefore, truly Sir, I think itt clear, that every Man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own Consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put Himself under."

To which Henry Ireton (Cromwell's son-in-law, and a representative of the Army high command) responded:

" ... no man hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom ... that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom."

Ireton's point was that citizenship, including the right to vote, was only for property owners, a principle that held fast in English law until 1918 (when, incidentally, property qualifications were introducedd for women, just as they were abolished for men). The army grandees listend politely to the arguments in 1647, but did not toleraate them after the talks broke up. In April, 1649, weeks after the execution of Charles I, an NCO and "Leveller," Robert Lockyer, faced a firing squad in the churchyard of Saint Paul's Cathedral, having been charged with mutiny against his officers. At his funeral, a procession of 3000 people included Parliamentary soldiers wearing the sea-green ribbons of the "Levellers." London "Levellers," including Thomas Lambe, are likely to have been in the crowd, and may have given speeches, although none have not been preserved.

The hopes of London radicals, such as Lambe, Prince, Overton, and Lilburne, were comprehensively dashed when Cromwell took power as Lord Protector in 1653. Thomas Lambe's conventicle had moved, by this stage, from Bell Alley to Smithfield, but we hear nothing of him beyond this date. We do not know the date of his death, or of Dorcas's, and, if they were buried in London, the records are likely to have been destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

The legacy of the "Levellers" proved to be far longer lived than the movement itself: many of their objectives, including manhood suffrage, were taken up by the Chartists, in the 1840s, although they, like the "Levellers" before them, failed to achieve these objectives in their lifetimes. Significantly, Chartist rhetoric drew explicitly on the example of the "Levellers," and of the 14th Century "Peasants' Revolt," more so than on the examples sof democracy or republicanism in the ancient world that had been favoured by some of the French Revolutionaries of the late 18th Century; or the more explicitly socialist themes that marked out 1848 as a "Year of Revolutions" in France, Germany, and Italy.

We do not, in any direct sense, have the "Levellers" to thank for our current parliamentary democracy, still less for our constitutional monarchy, which most of them would probably have opposed; but the 1640s saw the first moment in our history in which matters of constitutional government, as well as those of religious faith, were freely and openly discussed, not only in the corridors of power, but in taverns, and on the streets, and by "mechanicks," as well as by intellectuals, and by university-educated clergy.

Many of the ideas that first arose in this moment (manhood suffrage, religious tolerance, the abolition of imprisonment for debt) have been quietly incorporated into our law in the centuries that followed, whilst others (including biennial parliaments) have been dropped for good reasons. The debates themselves, however, continue, and it is in this broader sense, perhaps, that we are, all of us, the sons and daughters of that moment.

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from amazon.

Sunday, 6 December 2020

The Streets of Old Westminster: Apsley House and Hyde Park - Military London Past and Present

A visitor to London, exploring he City of Westminster, and having visited Green Park, can leave the park by the north-east gate, and turn left onto the south side of Piccadilly. A short walk, passing the RAF Bomber Command Memorial on the left, brings us to Hyde Park Corner, today a confusing "spaghetti junction" of roads and underpasses. In the middle of a traffic island sits the Wellington Arch, designed by Decimus Burton in the 1820s to commemorate the Duke's victory over Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo. There is a small exhibition space inside the arch, now managed by English Heritage, so it is sometimes possible to go inside.

|

| Wellington Arch. Photo: Carlos Delgado (CC-BY-SA). |

The Duke of Wellington himself took up residence in Apsley House, just to the north of the arch, in 1817, two years after the battle, as he planned a political career. Originally built in red brick, in the 1770s, to a design by Robert Adam, it was the Duke who added the facade of Portland stone (many London buildings, which appear to be of stone, are actually built of brick, with a similar stone facade. Apsley House, like Spencer House, is an early example of an aristocratic town house, built in the closing decades of the 18th Century, when the "London Social Season" was coming in to vogue.

|

| Apsley House. Photo: Viosan (licensed under GNU). |

Behind Apsley House is the Queen Elizabeth Gate, leading in to Hyde Park, the third and largest of the royal parks situated in close proximity to one another (the others being Saint James's Park and Green Park). Following the path to the north, known as Broad Walk, one passes a colossal statue of Achilles, on the right, also intended as a tribute to the Duke of Wellington and his victory. Designed by Richard Westmacott, it was inaugurated in 1822. As the first recorded example of a nude public statue in London, it attracted a good deal of public comment.

|

| Statue of Achilles. Photo: Andrew Dunn (licensed under CCA). |

|

| George Cruikshank's cartoon of the unveiling of the statue (image is in the Public Domain). |

Beyond Achilles is a more stark and modern memorial, to those killed in the terrorist atrocities in London on 7th July, 2005, a series of events that I remember well (my then girlfriend was close to the Russell Square bomb, shaken, though unhurt, but she was terrified that I might have gone to the British Library, and got caught up in the King's Cross bomb - in fact, I was at home, working on my biography of Sir John Lubbock).

The 7/7 Memorial sits on, or close to, the remains of a much earlier piece of London's military history. In 1642, as battle-lines were being drawn up between King Charles I and Parliament, the City of London declared for Parliament. The City's Militia, or "Trained Bands," which would, in time, become the backbone of the Parliamentary Infantry, now joined with thousands of Londoners to build an enormous earthwork, to defend not only "The City," but also the "West End," Lambeth, Southwark, and the docklands to the east.

|

| London's Civil War defences, as sketched by George Vertue in 1738 (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| The Roque Map (1746) showing the line of the Civil War earthworks running parallel to "Tyburn Lane" (now Park Lane). |

One corner of this earthwork must lie beneath Hyde Park, and run parallel to Park Lane (to our right). The management of the Royal Parks are convinced that its outline can be traced in the humps and bumps that are visible today, but other historians are sceptical. There has been a great deal of landscaping in the past two hundred and fifty years, and a geophysical survey (and, perhaps, excavation) would be necessary to distinguish, with any certainty, the earth moved in the 17th Century from that move in the 18th or the 19th. There can be little doubt, however, that the earthwork is there to be found, and, with it, a control point on the road leading from London to Oxford (today's Oxford Street and Bayswater Road), a likely entry point for Royalist spies.

|

| Possible earthwork, to the right of the 7/7 Memorial (photo: www.hydeparkknohow.uk). |

Hyde Park, as we see it today, was laid out in the 1720s, by Charles Bridgeman, working for George I. Its central water-feature, The Serpentine, was created by damming the Westbourne River. What had previously been a haunt of highwaymen, preying on travellers along the Oxford Road, and a duelling place for offended aristocrats, became a leisure ground for fashionable ladies. In 1851, the park hosted the Great Exhibition, with its Crystal Palace.

|

| Hyde Park from the air. Photo: Ben Leto (licensed under CCA). |

|

| The Crystal Palace (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| The Serpentine/ Photo: Jamie101 (licensed under CCA). |

|

| Hyde Park, by Camille Pissarro. Tokyo Fuji Art Museum (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| "Lady of Fashion of the 20th Century," by Claude Allin Shepperson, 1914 (image is in the Public Domain). |

The Military are still present, however. Gun salutes are fired from the park on State occasions, by the Royal Horse Artillery, and, as a sign of changing times, when I last witnessed this ceremony, the commanding officer was, for the first time, a woman. A barracks overlooks the park, and cavalry horses are still exercised along the "rides." What was once the western periphery of the metropolis now sits close to its centre.

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

Monday, 30 November 2020

Virtual Cultural Tourism: A New Departure

This is a very brief post, by way of an introduction to our new sister-site, Mark Patton Associates, where, for the first time, I am offering "virtual cultural tours," beginning with a four-day tour of Poland in December, 2020.

If, like many people that I know, your travel plans over the recent months have been frustrated by the circumstances of the lock-down, and the ongoing uncertainty of Brexit, such tours may well give you something to look forward to over the Christmas break, and into the New Year (we will be announcing new destinations in the coming months). Please click on the link above to learn more.

|

| Krakow's Wawel Castle from the River Vistula. Photo: EIGENWERK (licensed under GNU). |

If, on the other hand, virtual cultural tourism is simply not your thing, please don't worry - the focus of this site will continue to be on history and historical writing, as it always has been, and we will keep the two sites, and the two activities, entirely separate.

Saturday, 21 March 2020

The Streets of Old Westminster: Green Park and Spencer House.

|

| Canada Gate. Photo by Jordan 1972 (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Green Park. Photo by David Iliff (License CC BY-SA-3.0). |

The park was first enclosed, in the Sixteenth Century, by the Poultney family, and passed into the hands of the Crown in 1668. It was landscaped, in something like its present form, by John Nash, in 1820, the favoured architect of George IV, who shaped much of what we now think of as the "West End."

|

| Green Park. Phto by Jordan 1972 (image is in the Public Domain). |

Even before Nash's time, however, the fringes of Green Park had become fashionable as a location for the residences of the wealthy and powerful, those who had every reason to locate themselves in close proximity to the Royal Court. As the Eighteenth Century progressed, and the memories of Civil War faded, it became increasingly common for aristocratic families to spend at least part of the year in London. The idea of the "social season" was born: the German composer, George Frideric Handel, set up residence at London in 1713, anticipating the arrival of his patron, George, Elector of Hanover, soon to be crowned as George I of England. Handel brought with him new tastes in Italian opera, which many young aristocrats would have encountered in the course of their Grand Tours. Now they could enjoy it at the heart of their own capital city, and share the experience with their wives and families. Opera, however, was just one element of the social season, the main point of which was to see and be seen.

|

| Green Park, c 1833, by W. Schmollinger (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Green Park. Photo b Jordan 1972 (image is in the Public Domain). |

There is one aristocratic house overlooking Green Park, which can (in ordinary times, which these are not) be visited on Sundays. This is Spencer House, commissioned, in 1756, by John, the 1st Earl Spencer (an ancestor of the late Princess Diana). The exterior of the house was designed by John Vardy (a pupil of William Kent), and the interiors (largely) by James Stuart, recently returned from a sojourn in Athens, where he had drawn inspiration from ancient art and architecture that was beyond the reach of most "Grand Tourists." Tours of the house which must be booked in advance, take in the "State Rooms" (Ante-Room, Library, Dining Room, Palm Room, Music Room, Lady Spencer's Room, Great Room, and Painted Room), which, together, make up one of the earliest and finest examples of Neo-Classical domestic architecture in the British Isles (I am unable to post photographs of the interior here, but a virtual tour may be had on the Spencer House website).

|

| Spencer House in c 1800, by Thomas Malton Jr (image is in the Public Domain). |

The "social season" changed the face of London: aristocratic families arrived with retinues of servants, but word soon got around that there were opportunities in service in the capital, and the flow of migrants from the countryside to the capital increased. There were opportunities, too, in retail, and in related industries, such as dress-making and millinery. Great houses had much need of groceries, porcelain, glassware, furniture, and fabrics, and streets such as Piccadilly, Jermyn Street, and Saville Row, grew up to meet these needs. A handful of the businesses established at the time, such as Fortnum & Mason, are still trading today.

The world of Eighteenth Century London was one in which there were few restrictions on business, or limits to ambition, but it was also one without social protection or safety nets. In the words of John Gay's (1728) Beggar's Opera (itself a parody of the Italian operas playing in the West End): "The gamesters and lawyers are jugglers alike/If they meddle your all is in danger/like gypsies, if once they can finger a souse/Your pockets they'll pick and they'll pilfer your house/And give your estate to a stranger."

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be ordered from Amazon.

Monday, 6 January 2020

Great Books of 2019: The Matter of Troy Revisited

|

| Vase, found at Thebes, possibly depicting the abduction of Helen by Paris. Photo: British Museum. This vessel, dated c 735 BC, may have been made during Homer's lifetime. |

|

| Detail of the vase above. |

Homer and Vergil were epic poets, not historical novelists, and the novelist, unlike the poet, is almost invariably concerned with viewpoint, since that, arguably, is what makes the novel a novel. The default viewpoint of the epic poet is that of the rhapsode himself, even if he narrates through his protagonist (Odysseus, for example): he is omniscient; party even to the deliberations of the gods; and inevitably male. For Pat Barker, in The Silence of the Girls, and for Natalie Haynes, in A Thousand Ships, the point, then, is to tell the old story from new (and specifically female) viewpoints. Both of these novels take their lead from Homer's Iliad, and neither takes any great liberties with the story itself.

Barker takes (for the most part) a single female viewpoint: that of Briseis, the enslaved woman from a city allied to Troy, over whom Achilles and Agamemnon quarrel. She follows most of the conventions of the realist novel, and paints a vivid picture of life, in slavery, in an enemy camp. Barker is not the first novelist to narrate the story from Briseis's point of view (Judith Starkston does so in Hand of Fire, and with a good deal more historical attention to the cultural context of the Anatolian Bronze Age), but she does so with great humanity and compassion, and with an understanding of the realities of war that she has honed over years of writing about more recent conflicts:

"The hospital hut filled with men tossing and turning in sweaty sheets. The few brave enough to visit their friends carried lemons stuck with twigs of rosemary and bay, but nothing could keep the noxious fumes out of your lungs. This was not the coughing plague so some of those who fell ill did survive, but many didn't. By the end of the first week, men were dying in such numbers that funerals could no longer be dignified rituals honouring the dead. Instead, bodies were transported under cover of darkness t a deserted part of the beach to be disposed of as swiftly and secretly as possible. Corpse fires were visible from Troy and nobody wanted the Trojans to know how many Greeks were dying, so often five or six bodies would be thrown on to a single pyre."

Barker does, at times, depart from Briseis's viewpoint and narrates, either omisciently, or from the viewpoint of other characters (Patroclus, for example), but I found these departures distracting, rather than enlightening, given the clear focus of the novel as a whole.

Haynes, on the other hand, makes a virtue of her frequent switches in viewpoint: Briseis is one of her protagonists, but so is Calliope (the Muse of Epic Poetry), Creusa (the wife of Aeneas), Iphigenia (the daughter of Agamemnon), Penelope (the wife of Odysseus) and "The Trojan Women" as a group. Her descriptions of the squalor of the Greek camp were, for me, less vivid than Barker's, but this is balanced by the delightfully poignant humour of some of her viewpoints, notably Penelope's. Haynes draws, not only on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, but also on Euripides's Trojan Women and Hecabe, Vergil's Aeneid, and Ovid's Heroides.

"Sing Muse, he says, and the edge in his voice makes it clear that this is not a request. If I were minded to accede to his wish, I might say that he sharpens his tone on my name, like a warrior drawing his dagger across a whetstone, preparing for the morning's battle. But I am not in the mood to be a muse today. Perhaps he hasn't thought of what it is like to be me. Certainly he hasn't: like all poets, he thinks only of himself. But it is surprising that he hasn't considered how many other men there are like him, every day, all demanding my unwavering attention and support. How much epic poetry does the world really need?"

It is surely a misfortune, both for Barker, and for Haynes, that they embarked upon these projects at more or less the same time. They are very different writers, with very different approaches, and rather different backgrounds, but they have chosen the same material, the same events, the same characters, and I wonder how many readers will have the appetite for both? I read them both because the "reception" of Greek classics by later writers, including my own contemporaries, is one of the topics that I teach; but perhaps what is missing, in both cases, is something more than merely a different viewpoint (or set of viewpoints) to distinguish these works from all the reworkings that have come before?

Madeline Miller, in Circe, takes her inspiration from The Odyssey, rather than The Iliad. Again, the emphasis is on a different (and female) viewpoint, that of the witch, Circe, who turns Odysseus's men into pigs, and delays his return home. Circe, however, is immortal, and this creates a difficulty for a novelist. When I tell my students that the novel, as a literary form, is fundamentally concerned with viewpoint, I take for granted that the viewpoint is a human one, and that there is much that can remain unsaid, simply on the basis of our shared humanity: this includes our mortality, our sexuality (the fact of it, rather than its specific nature), our embededness in institutions and relationships that existed before we were born, and will continue to exist after we are dead. Circe is not human, and there is therefore much about her existence that cannot remain unsaid, that must rather be explained. I found these explanations a good deal more distracting than Barker's occasional shifts of viewpoint, precisely, in this instance, because I already understood the concepts that were being explained:

"The fury did not bother with lecture. She was a goddess of torment and understood the eloquence of violence. The sound of the whip was a crack like oaken branches breaking. Prometheus' shoulders jerked and a gash opened in his side long as my arm. All around me indrawn breaths hissed like water on hot rocks. The fury lifted her lash again ... The wounds of gods heal fast, but the Fury knew her business and was faster ... I had understood gods could bleed, but I had never seen it. He was one of the greatest of our kind, and the drops that fell from him were golden, smearing his back with a terrible beauty."

Miller does not confine herself to Homer's account: being immortal, Circe exists before Odysseus, and continues to exist after him (his departure from her island is, in a sense, the tipping point of the novel); like Haynes, she draws on other sources (one could almost believe that she has read the lost - or perhaps, mythical - Telegoniad, as well as the Iliad and Odyssey), and there is a twist in the tale of Circe's relationship with Odysseus. The twist, however, comes before the end, and that means that "the end," when it comes, is something of an anti-climax.

|

| The Sophilos Dinos, in the British Museum, made c 580-570 BC, and depicting the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (the parents of Achilles). |

Chigozie Obioma's An Orchestra of Minorities is a very different sort of novel: it is not a work of historical fiction, and does not share characters with, or recreate the events described in, Homer's Iliad or Odyssey. The Odyssey is invoked, but only a few times, and in passing (the protagonist has read a version of it a long time ago). What is shared with the Homeric epic is its broad themes and structure (a man leaves his homeland with a clear purpose in mind; he undertakes a long, arduous, and perilous journey; and ultimately returns, a changed and damaged man, to find that the realities that he thought he was coming back to have changed utterly).

The wanderer is not Greek, but Nigerian, and he travels, not as a warrior to Troy, but as a student to Northern Cyprus, where he finds that he has been deceived and defrauded by someone he had thought of as a friend. Like the other books here, Obioma's novel is bound up with mythology, but it is the mythology of the Igbo people of Nigeria, and it is only partially explained, which, for me, made the book more, not less, exciting. The viewpoint of the novel is not that of the protagonist, Chinonso, himself, but rather that of his Chi, a sort of guardian spirit, accountable, not to its human "host," but to the Igbo pantheon of deities and ancestral spirits.

"Chukwu, it struck him now, in this distant country of sky and dust and strange men, that what she feared that day had no happened to him. A poultry farmer named Jamike Nwaorji, having groomed him for some time, having plucked excess feathers from his body, having fed him with mash and millet, having let him graze about gaily, having probably staunched a leg wounded by a stray nail, had now sealed him up in a cage. And all he could do now, all there was to do now, was cry and wail. He had now joined many others, all the people Tobe had listed who had been defrauded of their belongings - the Nigerian girl near the police station, the man at the airport, all those who have been captured against their will to do what they did not want to do either in the past or the present, all who have been forced into joining an entity they do not wish to belong to, and countless others. All who have been chained and beaten, whose lands have been plundered, whose civilisations have been destroyed, who have been silenced, raped, shamed and killed. With all these people, he'd come to share a common fate. They were the minorities of this world whose only recourse was to join this universal orchestra in which all there was to do was cry and wail."

In the twenty-eight centuries since the death of Homer, his stories of the fall of Troy have been retold many times. Take, for example, the Ephaemeris Belli Trojani of Dictys Cretensis (c 350 AD), or the Roman de Troie of Benoit de Ste-Maure (c 1160), or the Historia Destructionis Troiae of Guido delle Colonne (c 1287): these texts are historically important, in that they kept those stories alive in a world in which Greek was no longer understood, but, in literary terms, they hardly rank as canonical. Those reworkings of the "Matter of Troy" (in Medieval Europe, it became subsumed under the "Matter of Rome," which, even before Vergil's time, was believed to have been founded by the descendants of Trojan refugees) that have really counted, that have shaped the development of European and World literature, have been those that have transformed, rather than those that have simply retold those stories: Vergil's focus on the journey of a refugee, rather than that of a conquering hero; Dante's elision of Classical and Catholic ideas of the afterlife; Milton's Protestant epic, which grants real agency to the universal anti-hero; and James Joyce's adoption of the epic idiom to the daily realities of life in early Twentieth Century Dublin. If we are looking, in this young century of ours, for an heir to this great tradition, my money would be on Chigozie Obioma.

|

| Roman Republican coin of C. Mamilius Limetanius (c 82 BC), depicting Odysseus. |

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

Sunday, 8 December 2019

The Ghosts of the Day: A New Short Story

|

| Theatres of the Boulevard du Temple, c 1862 (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Theatres of the Boulevard du Temple, c 1862, by Adolphe Martial Potemont (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Madame Saqui, from P. Ginisty (1907), Memoires d'une Danseuse de Cord, Private Publication (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| View of the Boulevard du Temple, by Louis Daguerre, 1838 or 1839 (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| A photographic laboratory of c 1840, reconstructed at the Musee Niepce, Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, Burgundy (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Detail of the picture above. |

early evening sky. Charles Bitry de Brullioles strode with purpose towards the Boulevard du

Temple, not to take his pleasures but to offer what help he could.

*****

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.