This blog-post is a summary of research that I carried out for the Worshipful Company of Tallow Chandlers, during the course of 2020 and 2021, and presented to the company in November, 2021. Thomas Lambe, a freeman of the company in the early decades of the 17th Century, was a soap-boiler (a producer of soap from rendered animal fat - an activity forming part of the craft and mystery of tallow-chandlery as defined at the time), who was also a controversial Baptist preacher, and a leading member of the "Levellers," a radical political movement agitating for universal manhood suffrage (the vote for every adult male), fixed-term parliaments, the abolition of capital punishment for theft, and the abolition of imprisonment for debt.

|

| London in the late 16th Century. |

|

| Illustration from The Declaration and Standard of the Levellers of England, 1649. |

Several of the most widely read recent books on the "Leveller" movement (a label rejected by most of its supporters, on the grounds that they did not support the "levelling of mens' estates," except on a purely voluntary basis), including John Rees's The Leveller Revolution, state that Lambe was one of two tallow chandlers involved in its leadership, the other being Thomas Prince. I did not, however, find Prince's name in the membership records of the company, and nor could I find any particular reason why Prince, who made his living as a cheese-monger, should have been a member of it. Prince is a fascinating historical figure in his own right, but my research focused on Thomas Lambe (to confuse matters further, there seem to have been two Baptist preachers named Thomas Lambe active in London at the same time; one described as a soap-boiler, the other as a merchant; and I am writing only about the former).

Thomas Lambe seems to have been born at Colchester, where he may also have served an apprenticeship as a tallow chandler and soap-boiler. I was unable to trace a baptismal record for him, but he did marry Dorcas Prentice there in 1619. Whilst living in Colchester, the couple fell foul of the authorities several times: they were excommunicated in 1636, for failing to attend (Anglican) worship, and for refusing to have one of their children baptised; the following year, still in Colchester, Thomas was arrested for "soap-boiling on the Sabbath."

Thomas Lambe seems to have taken up residence in London by 1624 (the date at which his name first appears in the membership records of the Tallow Chandlers). The fact that his name appears, in the 1620s and 1630s, both in London and in Colchester, might suggest that he and Dorcas had two homes, the one in Colchester very possibly shared with one or more of their parents. Thomas was imprisoned in the Fleet Gaol in 1640, for unlicensed preaching in Whitechapel (provoking a riot when constables attempted to break up the meeting); but, by 1641, had established a Baptist congregation in Bell Alley (off Coleman Street, near the Guildhall); by this time, he seems to have been permanently resident in London. He undertook several preaching tours of England, visiting Guildford, Portsmouth, & Devizes; and baptising people in the Severn and the Colne (he seemingly had more sense than to do so in the filthy waters of the Thames at London).

|

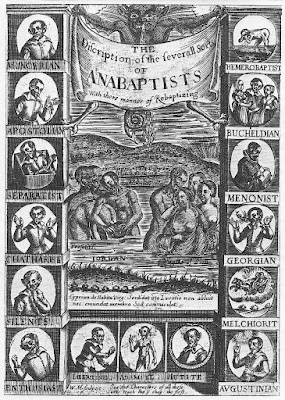

| "The Dippers Dipp'd," from an anti-Baptist pamphlet by Daniel Featley (1649), portraying Baptists as schismatics. |

Lambe's congregation in Bell Alley soon gained a reputation for religious radicalism. The Presbytereian, Thomas Edwards, complained about the role of "mechanicks" (artisans and working people, without formal training in theology) in preaching: Lambe even encouraged women, including a lace-maker, Mrs Attaway, to preach in his church, someting that would not have been permitted in more conventionally "Puritan" congregations (few people in 17th Century England considered themselves to be "Puritans" - the term was almost always used in a derogatory sense, to refer to people who saw themselves as Presbyterians, "Independents" - in modern terms Congregationalists, Baptists, and Quakers). Edwards (whose agenda was to extinguish all forms of "Puritanism" other than his own) raised further objections to Lambe's congregation:

"Many use to resort to this church and meeting, the house and yards full, especially young youths and wenches flock thither ... in the latter end of the Lord's Day, many persons, some from the separate churches [Independent, Quaker], others from our churches [formerly Anglican, converted to Presbyterian worship], will go to this Lambe's church for novelty, because of the disputes and wranglings that will be there upon questions ... several parties in one room, some speaking in one part, some in another ... "

|

| Bell Alley, 17th Century plan. |

Among the questions thus debated by Lambe's congregants was the suggestion, heretical to men such as Edwards, of "universal reconciliation," according to which everyone (or, at the very least, all Christian believers) would ultimately be saved, through the boundless love and grace of Jesus Christ.

Lambe was a close associate of Richard Overton, also a Baptist (and thus probably a member of Lambe's congregation), and a "Leveller," who ran an undreground printing operation from Bell Alley.

The Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, holds one of very few surviving copies of Lambe's Treatise of Particular Predestination, printed by Overton, which argues that:

" ... the spirit of the Gospel, which holds forth Christ's giving himself, a ransom for all men [1 Tim, 6], a propitiation for the sinnes of the whole world [1 John, 2,2], and that he tasted death for every man [Heb.2.9], which is such a glorious truth, as without which first the Gospel of God's free grace cannot be preached to all men."

He goes on, in this pamphlet, to argue against the Calvinist notion (accepted by most Presbyterians and Independents, as well as by many less radical Baptists) that only some people have been chosen by God for salvation.

In 1641, as the battle lines were being drawn up between Charles I and Parliament, "Puritans" within the City of London (already, probably, in a small majority) staged an effective coup, replacing all, or nearly all, of the Anglicans and Royalists on the Common Council with Presbyterians and Independents whose loyalty was to Parliament. Isaac Pennington became the first in a line of "Puritan" Lord Mayors. The new administration quickly formed a "Committee of Safety," and took control of the "London Trained Bands." This militia, which had served for many years as a police and civil defence force, and as an informal fire brigade, would become the backbone of the Parliamentary Infantry, under the command of Philip Skippon, a Presbyterian who had served as a mercenary, on the Protestant side, in the Thirty Years War in Germany. If Thomas Lambe had ever served in the Trained Bands, it would have been in the 1620s, when he was first living in London. Although we do not know when he was born, his date of marriage suggests that, by the 1640s, he would probably have been considered too old for front-line military service.

Whilst he probably played no active role in the civil wars themselves, he was certainly engaged in the attempt to define the new society that it was hoped would emerge from them. Together with his friends, the printer, Richard Overton; the cheese-monger, Thomas Prince; and other prominent Londoners, including John Lilburne; he was a member of the "Levellers," a movement which some have seen as England's first political party. Initially, in the 1640s, it was a loose alliance of men, who met to discuss political topics, in taverns including The Windmill and The Whalebone, both in Lothbury. One such discussion group was the "Robin Hood Club," and the association with the legendary outlaw was more than accidental. Later, members of these various discussion groups took to wearing a sea-green ribbon, as a means of identifying themselves.

A "Leveller" manifesto of 1649, signed by Lilburne, Prince, and Overton, sets out what they thought to be at stake: " ... an opportunity which, these 600 years, has been desired, but could never be obtained, of making this a truly happy and wholly free nation ... "

|

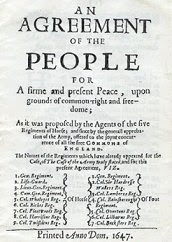

| A "Leveller" manifesto, 1647. |

The "Levellers" seem to have been a genuinely grass-roots movement, led by artisans and "mechanicks," rather than by intellectuals. Leaving aside John Milton's Areopagitica (1644), which many of these men might indeed have read, but the title of which probably meant little to them, radical tracts of the time, including "Leveller" pamphlets, do not draw their inspirations from the examples of either the Athenian Democracy, or the Roman Republic, nor do they make reference to the constitutional example of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Instead, they draw on folk traditions of Anglo-Saxon resistance to Norman rule (seeing Charles Stuart as the successor of William the Conqueror), including the mythical example of Robin Hood, and the supposedly "consensual" or constitutional basis of rule by the Anglo-Saxon Kings, including Alfred the Great.

Here, for example, is Gerard Winstanley, writing in 1649 (and criticising not Charles Stuart, who by that stage was dead, but the "Puritan" establishment of the Commonwealth itself):

"O what mighty delusion, do you, who are the powers of England, live in! That while you pretend to throw down the Norman yoke, and Babylonish power, and have promised to make the groaning people of England a Free People; yet you still lift up that Norman yoke, and slavish tyranny, and holds the People as much in bondage, as the Bastard Conquerour himself, and his Councel of War."

The "Leveller" manifestoes of 1648-49 were radical indeed, including commitments to "manhood suffrage" (the right of every man, possibly excluding servants, to vote); fixed term (biennial) parliaments; "absolute" freedom of religion (it is a little unclear whether this was intended to include Roman Catholics or Jews); the abolition of capital punishment for theft; and the abolition of imprisonment for debt. For so long as these were simply matters for discussion in London taverns, Presbyterians and "Silken" (presumably well-heeled and socially conservative) Independents paid little attention to them, but, by 1647, "Leveller" opinions were gaining currency within the ranks of the New Model Army, which senior commanders, including Oliver Cromwell, took far more seriously.

In the Putney Debates, chaired by Cromwell, and prompted by arrears in pay to soldiers, the "Leveller," Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, argued that:

"I think that the poorest hee that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest hee; and therefore, truly Sir, I think itt clear, that every Man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own Consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put Himself under."

To which Henry Ireton (Cromwell's son-in-law, and a representative of the Army high command) responded:

" ... no man hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom ... that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom."

Ireton's point was that citizenship, including the right to vote, was only for property owners, a principle that held fast in English law until 1918 (when, incidentally, property qualifications were introducedd for women, just as they were abolished for men). The army grandees listend politely to the arguments in 1647, but did not toleraate them after the talks broke up. In April, 1649, weeks after the execution of Charles I, an NCO and "Leveller," Robert Lockyer, faced a firing squad in the churchyard of Saint Paul's Cathedral, having been charged with mutiny against his officers. At his funeral, a procession of 3000 people included Parliamentary soldiers wearing the sea-green ribbons of the "Levellers." London "Levellers," including Thomas Lambe, are likely to have been in the crowd, and may have given speeches, although none have not been preserved.

The hopes of London radicals, such as Lambe, Prince, Overton, and Lilburne, were comprehensively dashed when Cromwell took power as Lord Protector in 1653. Thomas Lambe's conventicle had moved, by this stage, from Bell Alley to Smithfield, but we hear nothing of him beyond this date. We do not know the date of his death, or of Dorcas's, and, if they were buried in London, the records are likely to have been destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

The legacy of the "Levellers" proved to be far longer lived than the movement itself: many of their objectives, including manhood suffrage, were taken up by the Chartists, in the 1840s, although they, like the "Levellers" before them, failed to achieve these objectives in their lifetimes. Significantly, Chartist rhetoric drew explicitly on the example of the "Levellers," and of the 14th Century "Peasants' Revolt," more so than on the examples sof democracy or republicanism in the ancient world that had been favoured by some of the French Revolutionaries of the late 18th Century; or the more explicitly socialist themes that marked out 1848 as a "Year of Revolutions" in France, Germany, and Italy.

We do not, in any direct sense, have the "Levellers" to thank for our current parliamentary democracy, still less for our constitutional monarchy, which most of them would probably have opposed; but the 1640s saw the first moment in our history in which matters of constitutional government, as well as those of religious faith, were freely and openly discussed, not only in the corridors of power, but in taverns, and on the streets, and by "mechanicks," as well as by intellectuals, and by university-educated clergy.

Many of the ideas that first arose in this moment (manhood suffrage, religious tolerance, the abolition of imprisonment for debt) have been quietly incorporated into our law in the centuries that followed, whilst others (including biennial parliaments) have been dropped for good reasons. The debates themselves, however, continue, and it is in this broader sense, perhaps, that we are, all of us, the sons and daughters of that moment.

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from amazon.

Excellent article, Mark!

ReplyDelete