In an earlier blog-post, I explored the emergence and development of the Medieval cult of Saint James at Compostela. The cult has its origins in the 9th Century, but it would not have developed into the international pilgrimage phenomenon that was "The Way of Saint James," were it not for a 12th Century document signed in the name of Pope Callixtus II (1065-1124). The document, however, is a forgery, written at least a decade after Callixtus's death.

Callixtus II, Pope from 1119 to 1124 (image is in the Public Domain).

Illustration of the Apostle James, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (image is in the Public Domain).

The Codex Callixtinus, or Liber Sancti Jacobi, the original copy of which is held by the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela (it was stolen in 2011, but recovered a year later), and was probably written between 1135 and 1145. One of its authors appears to have been a French cleric by the name of Aymeric Picard. It consists of five books which, between them, define aspects of the cult of Saint James, making this the best documented of all Medieval pilgrimage cults.

1. The Book of the Liturgies, including a sermon, supposedly written by Callixtus, to be preached to pilgrims, as well as some of the earliest surviving liturgical music.

2. The Book of the Miracles, documenting the miracles performed by Saint James at the shrine of Compostela.

3. The Transfer of the Body to Santiago, an account of the miraculous translation of Saint James from the Holy Land to Compostela.

4. The History of Charlemagne and Roland, a heavily mythologised account of their battles in Spain, explicitly linking them to the cult.

5. A Guide for the Traveller, a practical guide to the principal routes through France and Spain to Compostela.

Illustration of Charlemagne and his knights on the road to Compostela, from the original copy of the Codex Callixtinus (image is in the Public Domain).

It is known that a copy was made in 1173 by a monk, Arnaldo de Monte (this copy is now in Barcelona), and it is likely that other copies were held in various monastic houses around Europe. It is unlikely that pilgrims actually carried copies of the travellers' guide on the road (manuscripts hand-written on vellum were both expensive and delicate). Canons from the monastic houses probably studied the documents in their own scriptorums, and then acted as guides.

This, however, leaves open the question as to who was responsible for the forgery. Aymeric Picaud may have researched the travellers' guide, but he is surely too obscure a figure to have contrived the entire enterprise on his own. A clue may be found in the dedication of the opening letter, supposedly written by the Pope: it is addressed to "The holy assembly of the Basilica of Cluny, and Diego, Archbishop of Compostela."

Nobody had more to gain from the enterprise than Archbishop Diego Gelmirez and his See, so he can hardly be free from suspicion. It is interesting that, among the great innovators of the Medieval Church, he stands out as a figure who was never canonised, so perhaps this suspicion weighed heavily in the balance.

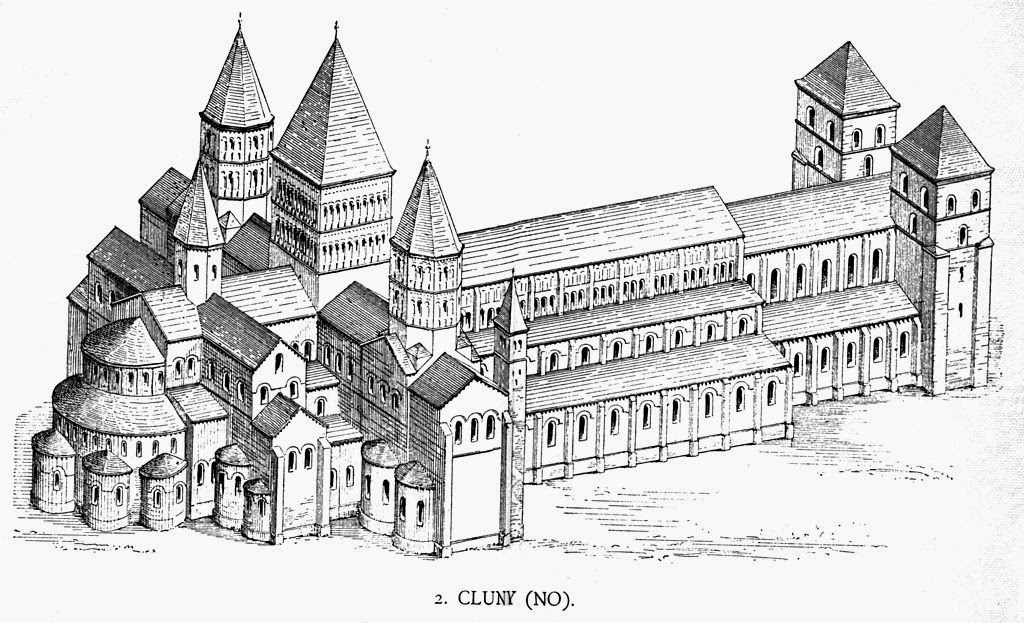

Reconstruction of the Medieval Abbey of Cluny, by Georg Delvio & Gustav von Bezold (image is in the Public Domain).

The Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy, was perhaps the wealthiest monastic house of its time, its abbot answerable only to the Pope. This abbot, at the time, was Peter the Venerable, another leading churchman who was never formally canonised, although he has sometimes been honoured as if he were a saint.

Peter the Venerable, with three of his monks. 13th Century Manuscript, Bibliotheque Nationale de France (image is in the Public Domain).

Peter was, by the standards of his day, an ecclesiastical moderate: he had travelled in Spain, conversing with Islamic scholars; and commissioned the first Latin translation of the Koran. His commentary identified Islam as a "heresy," but he did not condemn it without first seeking to understand it. Peter the Venerable also gave sanctuary to the theologian, Peter Abelard, after he had been condemned by Bernard of Clairvaux. Might he, then, as Bernard preached the Second Crusade, have conspired with Diego Gelmirez to send pilgrims in the opposite direction, both geographically and spiritually, on the peaceful road to Compostela? We may never know the full truth, but the "Way of Saint James" would long outlive both Diego Gelmirez and Peter the Venerable, and provide a model for the development of later pilgrimage cults, including that of Saint Thomas a Becket at Canterbury.

Mark Patton's novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

_F0173k.jpg)

Fascinating post,Mark, thank you.My Chilean grandmother and my mother were always talking about when they went to Compostela, even though they didn't go on The Way by foot. And your suggestion about sending pilgrims the opposite way makes for an interesting conclusion.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Roland! My Irish Catholic relatives always headed for Lourdes rather than Compostela (not nearly as interesting historically): I think it had to do with the fact that their parish priests all belonged to the Order of Mary Immaculate. My hypothesis about Peter and Bernard is, sadly, untestable, until such time as we can date the manuscript more accurately than is currently possible.

ReplyDelete